Honestly, trying to sit down and write this blog post has been a lot more challenging than I anticipated. All of my other final assignments have just been a regurgitation of facts, so switching gears to form my own opinions has been weird. I can tell you why Pluto is no longer considered a planet and trace the path of Alcibiades’ capricious loyalties all through Ancient Greece. My brain physically ached for a while from so much cramming, although that’s not even possible since the brain has no pain receptors. But, a broad question like “What has the point of this semester been?” is a whole different playing field. I drew a mental blank for three days before I even tried to sit down and write. Continue reading “A Step Back From The Semester”

Who Do You Think You Are?

Throughout both of Lewis Carroll’s works Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, language conventions and linguistics are turned on their head. Commonplace words and phrases are used outside of their familiar meanings, sometimes so literally that attempting to find a figurative meaning can only leave the reader befuddled. One very unique instance where Carroll uses this technique is in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in the fifth chapter entitled “Advice from a Caterpillar.” During Alice’s conversation with the Caterpillar, she is asked two very distinct questions. “Who are you?” and “Who are you?” The same three words, but two very different meanings. The first is exactly what it sounds like. Upon first noticing Alice, the Caterpillar asks her to introduce herself. She has difficulty coming up with an answer for his inquiry, though, having only just finished arguing with herself about whether or not she is really Alice or if she had somehow changed into another little girl. At this moment, her own identity is a mystery to her.

But what is interesting is the second posing of the question.

‘Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,’ said Alice; ‘all I know is, it would feel very queer to me.’

‘You!’ said the Caterpillar contemptuously. ‘Who are you?’

No longer is the Caterpillar asking Alice to identify herself. This question has a bitter edge to it that implies it asks more than a name; the words may have been “Who are you?” but the question was “Who do you think you are?” It is meant as a sarcastic comment, but it raises an interesting question.

Are who you are and who you think you are two different things? And if so, which is more important? Even as Alice stumbles along trying to figure out if she is Alice or Ada or Mabel, is she ever anything other than Alice? Does her belief that she must be someone else make it so? Facing the two questions by the Caterpillar, Alice does not answer either of them because she does not have the answers. She does, however, go on to explain that, out of everything, she would feel more herself if she could regain her old height. Although Alice is still Alice, she sees herself a certain way and finds her security in identity in that self-image. She is not Alice if she does not fit that image, so, at least for her, who she is and who she thinks she is are separate but dependent things. In this way, even if Alice is still Alice, who Alice thinks she is is what matters the most.

Physicality vs Substance

The ambiguity of identity is what makes it so convoluted in formulating a direct definition to encapsulate it’s core idea. The direct definition of identity is ‘the fact of being who or what a person or thing is’. However, that interpretation of identity leaves many blank spaces in the answer to our question; What actually is identity? Is it the state of being, or is it the narrative of being a physical entity. We are given the idea that a person or thing is tied to a singular identity, however, when we change those circumstances, does it retain its identity?

In class, we briefly discussed the issue of identity in defining a book and whether it is the narrative of the book, or its physicality, that represents that definition. In Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, questioning identity is a reoccurring and prominent theme. Multiple times, the story makes Alice and the reader question the reality of the situations. However, not all these questions of identity stem from Alice’s time in Wonderland. In the very beginning of the story, Alice and her sister were laying under a tree while Alice’s sister ‘read’ a book. “Once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, ‘and what is the use of a book,’ thought Alice ‘without pictures or conversations?'”. The purpose of the ‘book’ is not the focus of this blog post, but rather the definition of such object as a book. Is the identity of the book validated by the physicality of the material its made of, or rather the narrative its meant to have?

The identity of the book in regards to the passage is ambiguous because of the lack of answer. the passage toys with the question because Alice leaves it open for interpretation. As we have seen from class, the answer to this is up to perspective. Many people may side with the physicality of the book as what defines its identity, while some may side with the narrative. However, maybe identity should stay ambiguous. Let it be what it is.

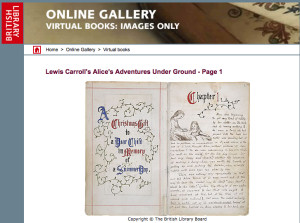

Alice’s Adventures Underground at the British Library

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

In class, we discussed the 1903 silent film version of Alice. You can find that at the Internet Archive.