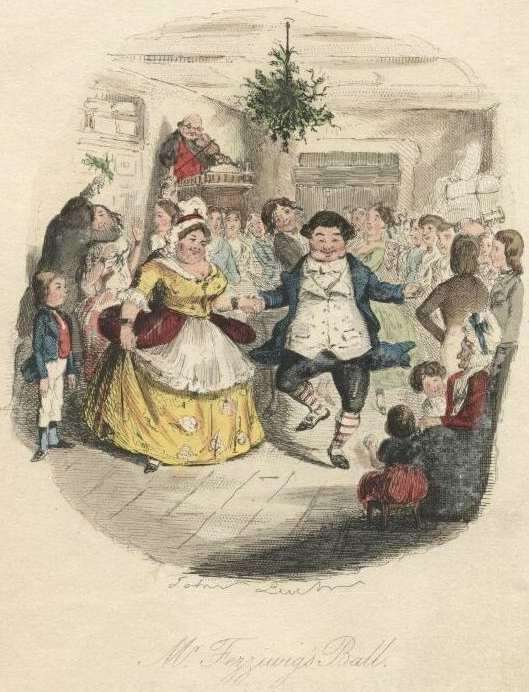

Today’s theme song in ENGL 203-04 is “Sir Roger de Coverley.” It’s really a dance rather than a song, as explained below.

Dickens refers to this traditional English country dance in his description of Fezziwig’s ball in “Stave Two” of A Christmas Carol:

There were more dances, and there were forfeits, and more dances, and there was cake, and there was negus, and there was a great piece of Cold Roast, and there was a great piece of Cold Boiled, and there were mince-pies, and plenty of beer. But the great effect of the evening came after the Roast and Boiled, when the fiddler (an artful dog, mind! The sort of man who knew his business better than you or I could have told it him!) struck up “Sir Roger de Coverley.” Then old Fezziwig stood out to dance with Mrs. Fezziwig. Top couple, too; with a good stiff piece of work cut out for them; three or four and twenty pair of partners; people who were not to be trifled with; people who would dance, and had no notion of walking.

In The Annotated Christmas Carol, Michael Patrick Hearn gives this explanation of “Sir Roger de Coverley”:

Also known “slip or Sir Roger,” [it is] a dance similar to the Virginia reel. Sir Richard Steele (1672-1729) took the name for a member of the fictitious club of The Spectator (March 2, 1711); his great-grandfather supposedly invented the dance. It was first described in John Playford’s Dancing Master (1692): the first man goes below the second woman, then round her, and so below the second man into his own place; then the first woman goes below the second man, then round him. and so below the second woman into her own place; then the first couple cross over below the second couple, and take hands and turn round twice, then leap up through and cast off into the second couple’s place. Dickens describes a more complex pattern, with steps borrowed from other dances. Sir Roger de Coverley was the most raucous and best known of country dances in the nineteenth century and traditionally the last one performed on a night of merrymaking. It was a bit out of fashion at the time of the story, however. “Country dances being low, were utterly proscribed,” Dickens notes in Chapter 8 of The Old Curiosity Shop (1841). The quadrille was considered far more chic at the time. A Christmas Carol and its dramatizations may well have done much to revive Sir Roger de Coverley in the cities. (W.W. Norton, 1976, pp. 70-71).

On their Library of Dance website at the University of Texas at Austin, Nick and Melissa Enge offer a detailed discussion of the dance that includes diagrams, historical and literary references, and a list of options for the music, typically in 9/8 or 6/8 time. “[F]or the early 19th century (i.e., a Regency Sir Roger), use a slip-jig (in 9/8),” write the Enges, linking to this sample from Spare Parts. The early nineteenth century is the appropriate time period for Scrooge’s youth.

As the Enges point out,

Many 19th century sources propose that Sir Roger De Coverley was (and should be) danced as the final dance of the evening. For example, in Thomas Wilson’s The Complete System of English Country Dancing (c. 1820) he proposes that: “At all Balls properly regulated, this Dance should be the finishing one, as it is calculated from the sociality of its construction, to promote the good humour of the company, and causing them to separate in evincing a pleasing satisfaction with each other.” Likewise, Routledge (1868) writes that “Sir Roger de Coverley is always introduced at the end of the evening; and no dance could be so well fitted to send the guests home in good humour with each other and with their hosts.”

This description illuminates the symbolic significance of the dance in the Carol. Its inherent sociality is a contrast to Scrooge’s present-day wish to be (as he tells the charitable gentlemen in Stave One) “left alone.” We might say the same, more broadly, of Fezziwig’s party, and we might think, in this connection, of the significance that Clarissa Dalloway’s parties hold for her in Woolf’s novel, as an opportunity to bring disparate and disconnected people together in one place in an act of creation that she imagines as an “offering” to life.

Finally, in thinking about parties as a meaningful human activity, we might remember what Alasdair MacIntyre says about those strains of thought in philosophy and the social sciences that attempt to take de-contextualized human “actions” as a fundamental unit; by contrast, he argues, “an intelligible action is a more fundamental concept than that of an action as such” — actions taking their intelligibility from the narratives to which they belong. To put this another way, the things humans do always have meaning built into them. Because we’re meaning-making animals, there’s no way to understand the things we do apart from the meanings those doings have for us.

If true, this fact about human beings has two consequences relevant to our studies in ENGL 203. To begin with, we can think of the arts in general, and literature in particular, as a realm in which creative individuals leverage socially meaning-laden stories and symbols to offer new ways of finding meaning in human experience. Partying is a socially meaning-laden activity that both Dickens and Woolf leverage, in a second-order act of meaning-making, to say something meaningful about the relationship between individuals and society.

It follows, then, that the study of the arts generally, and of literature in particular, represents a third-order act of meaning-making whose purpose is to say something meaningful about the ways in which individual artists, and the arts collectively, make meaning.

What form does this study take? To come satisfyingly full-circle, we’ve already seen that for Kenneth Burke, it basically takes the form of … a party. And it’s a party whose central activity, in Burke’s account, is more or less an elaborate social dance in words:

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.