Honestly, trying to sit down and write this blog post has been a lot more challenging than I anticipated. All of my other final assignments have just been a regurgitation of facts, so switching gears to form my own opinions has been weird. I can tell you why Pluto is no longer considered a planet and trace the path of Alcibiades’ capricious loyalties all through Ancient Greece. My brain physically ached for a while from so much cramming, although that’s not even possible since the brain has no pain receptors. But, a broad question like “What has the point of this semester been?” is a whole different playing field. I drew a mental blank for three days before I even tried to sit down and write. Continue reading “A Step Back From The Semester”

The Tradition of the Christmas Carol

I grew up surrounded by literature. My dad is an English professor with a specialty in Early American Literature, it’s just always been a huge part of my life, even to the point that Edgar Allan Poe was my bedtime stories.

My favorite way that my dad’s profession bled into our home life, though, was always his colleagues and the talks that he would let me come with him to see. I love to hear people talk about what they are passionate about and do what they love, so I tagged along to as many presentations as I could.

The best event my dad ever brought me to was Dr. Marc Napolitano’s performance of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. Dr. Napolitano was relatively new to the department that year – I think it was 2013 – and I hadn’t met him before, so I wasn’t sure what to expect. I knew the story of A Christmas Carol, everyone knows the story. I’d never read it, I was still in middle shool, but I was familiar with the plot. I’d seen renditions of it through disney animations and such. Worst case scenario, what I was walking into was some professor standing in front of a crowd and droning on about the significance of the story or something else that wouldn’t hold my attention.

It absolutely was not that.

For two hours, I sat next to my dad, absolutely riveted by Dr. Napolitano as he stood in front of a full room of students and other professors and gave a one man performance of A Christmas Carol, with voices and expressions and a passion that I’d never seen before. He was the only person up there, but each character was unique and all it took was a shift of his shoulders and a different lilt to his words for me to know that someone different was speaking. He was phenomenal. This was A Christmas Carol as it was supposed to be.

Looking back on it now, Dr. Naoplitano’s performance was a perfect example of how little it takes for an old work to take on new life. He was so passionate about this text that he was willing to memorize it in its entirety and stand in front of a crowd to bare his heart as he performed it so that he could share it with others the way he saw it, which was no small feat especially since Dr. Napolitano was a small, quiet man with a gentle smile and an even gentler voice. None of his shyness was present during his performance, his voice was booming. Even now I can hear him.

“Are there no prisons?! Are there no workhouses?!”

The fluidity of A Christmas Carol comes to my mind as we start to tackle it in class. After seeing that performance, I’ll be honest, no other adaptation of Dickens’ work has been good enough for me. Somehow, Dr. Napolitano had taken this thing that so many people knew by heart and made it his own. He made it new and he made it riveting, and I know all too well how hard it is to make a room full of cadets at USMA pay attention for that long.

After that first performance and until three years later when Dr. Napolitano left the academy, my family made it a tradition to go see his performance. In 2015, he left USMA and accepted a job offer at USAFA, and my childhood best friend who is a current cadet there assures me he’s still continuing his tradition of sharing Dickens’ A Christmas Carol with anyone willing to listen.

Thursday theme – White Rabbit

Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is “White Rabbit,” written by Grace Slick when she was a member of the short-lived group The Great Society, and performed by her here as lead singer of Jefferson Airplane. This version, recorded at the 1969 Woodstock music festival, is only slightly different from the one on the Airplane’s 1967 album Surrealistic Pillow but quite different from the Great Society’s 1966 live performance in San Francisco. If you’re in the mood for some mind-blowing retro psychedelic TV, you can also watch this 1967 TV performance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Among works that inspire what we’ve been calling follow-on creativity, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are practically without rival. In his 1995 Lewis Carroll: A Biography (Knopf), Morton N. Cohen writes,

. . . neither Alice book has ever gone out of print. . . . Next to the Bible and Shakespeare, they are the books most widely and most frequently translated and quoted. Over seventy-five editions and versions of the Alice books were available in 1993, including play texts, parodies, read-along cassettes, teachers’ guides, audio-language studies, coloring books, “New Method” readers, abridgments, learn-to-read story books, single-syllable texts, coloring books, pop-up books, musical renderings, casebooks, and a deluxe edition selling for £175. They have been translated into over seventy languages, including Swahili and Yiddish; and they exist in Braille.

(pp. 134-35)

Thursday theme – The Tyger

Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is a musical setting of the English poet William Blake’s “The Tyger,” composed by Andrew Miller and performed here by the Concordia Choir.

Each of the poems we’re looking at today — including Blake’s “The Tyger” — exists in multiple versions. This is what makes them fluid texts. But what do we mean by a version? Continue reading “Thursday theme – The Tyger”

Tuesday theme – My Country Used To Be

Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is “My Country Used to Be,” written and performed here by jazz singer-songwriter Dave Frishberg. Frishberg composed the song in the aftermath of the United States’ 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The mood of Frishberg’s song is quite different from that of Thoreau’s “Resistance to Civil Government,” written in protest of both slavery and the U.S. war with Mexico. Thoreau’s essay expresses outrage; this feels more like a lament. Despite the difference in mood, both express dissatisfaction with things as they are. Frishberg’s point of comparison is America as (he believes) it once was, while Thoreau’s is a “higher law” that America has failed to meet since its birth as a state whose founding legal document countenanced slavery.

Both represent contributions to the “unending conversation” among citizens of the United States as to what their country is, has been, and should be.

Thoreau makes his contribution through argument, using his night in jail (for refusing to pay the poll tax) as a springboard to explore the circumstances under which we do or don’t owe the law, or the state, our allegiance. Frishberg makes his contribution by re-purposing a patriotic melody — “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” — to convey his vision of an America that has lost its way.

Interestingly, we might understand Frishberg’s contribution to the conversation as itself an act of “resistance” or “civil disobedience.” In effect, he occupies “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” (as well as “Yankee Doodle Dandy”) in much the way street protesters occupy public spaces for a march or demonstration.

By occupying patriotic music with subversive intent, Frishberg participates in a venerable tradition. Even “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” belongs to this tradition, consisting as it does of lyrics praising America put to the tune of “God Save The Queen,” a patriotic song of America’s former colonial ruler, Great Britain.

“The Star Spangled Banner” has been occupied many times. In 1844, two years before Thoreau’s arrest in Concord, the abolitionist newspaper Song of Liberty published E.A. Atlee’s powerful four-verse “Oh Say, Do You Hear?” Here’s just the first verse:

Oh, say do you hear, at the dawn’s early light,

The shrieks of those bondmen, whose blood is now streaming

From the merciless lash, while our banner in sight

With its stars, mocking freedom, is fitfully gleaming?

Do you see the backs bare? Do you mark every score

Of the whip of the driver trace channels of gore?

And say, doth our star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave?

You can read the other three verses (and hear “Oh Say, Do You Hear?” performed) on the website Star Spangled Music, which provides an extensive guide to the history and cultural significance of the national anthem.

One of the boldest and most remarkable recent occupations of the anthem was executed in 2008 by jazz singer René Marie, invited to sing “The Star Spangled Banner” before Denver mayor John Hickenlooper’s State of the City address. She plugged in the words to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” also known as “The Black National Anthem.” The mayor was not amused, and the governor, Bill Ritter, labeled the performance “disrespectful.”

Felix Contreras discusses Marie’s and four other memorable performances of the national anthem in his 2009 report for National Public Radio, “The Many Sides Of ‘The Star Spangled Banner.'” At least three of these performances (by José Feliciano, Jimi Hendrix, and Marvin Gaye) might also be seen as occupations of a kind — not through the substitution of new words for the traditional ones, but simply through their re-interpretations of the melody. Listening to Feliciano’s quiet and soulful version, performed before Game 5 of the 1968 World Series, it’s hard to believe that he, too, was accused of disrespect. Was it really his version of the music people objected to? Or was it the fact of his laying claim simultaneously to his Puerto Rican and American identities through the re-mixing of musical traditions?

One may also wonder how much any of those who found Feliciano’s rendition disrespectful actually knew of the anthem’s history, and whether any of them realized how distant their idea of a “normal” rendition was from the way it would have been performed in Francis Scott Key’s time.

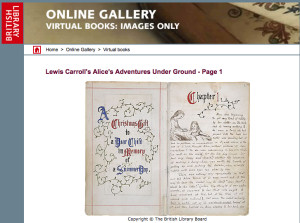

Alice’s Adventures Underground at the British Library

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

In class, we discussed the 1903 silent film version of Alice. You can find that at the Internet Archive.