Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is “White Rabbit,” written by Grace Slick when she was a member of the short-lived group The Great Society, and performed by her here as lead singer of Jefferson Airplane. This version, recorded at the 1969 Woodstock music festival, is only slightly different from the one on the Airplane’s 1967 album Surrealistic Pillow but quite different from the Great Society’s 1966 live performance in San Francisco. If you’re in the mood for some mind-blowing retro psychedelic TV, you can also watch this 1967 TV performance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Among works that inspire what we’ve been calling follow-on creativity, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are practically without rival. In his 1995 Lewis Carroll: A Biography (Knopf), Morton N. Cohen writes,

. . . neither Alice book has ever gone out of print. . . . Next to the Bible and Shakespeare, they are the books most widely and most frequently translated and quoted. Over seventy-five editions and versions of the Alice books were available in 1993, including play texts, parodies, read-along cassettes, teachers’ guides, audio-language studies, coloring books, “New Method” readers, abridgments, learn-to-read story books, single-syllable texts, coloring books, pop-up books, musical renderings, casebooks, and a deluxe edition selling for £175. They have been translated into over seventy languages, including Swahili and Yiddish; and they exist in Braille.

(pp. 134-35)

I grew up in a house that had previously been the home of Anna Richards Brewster, who illustrated one of those examples of follow-on Alice creativity, A New Alice in the Old Wonderland (1895), written by her mother, Anna M. Richards. Anna Richards’s husband, the father of Brewster, was the artist William Trost Richards, one of whose seascape paintings hangs in the residence of the SUNY Geneseo president.

Of the numerous film adaptations of the Alice books, the best known may be Walt Disney’s 1951 animated version. If you’re interested in cinema history, you may also want to have a look at this 1903 silent version.

So based simply on its afterlife, one would be hard pressed to find a more fluid text than that of the girl who famously begins her adventures — best understood, perhaps, as adventures in fluidity — by falling into a pool of her own tears. But the Alice books also serve as an excellent example of a text whose fluidity precedes its appearance in print.

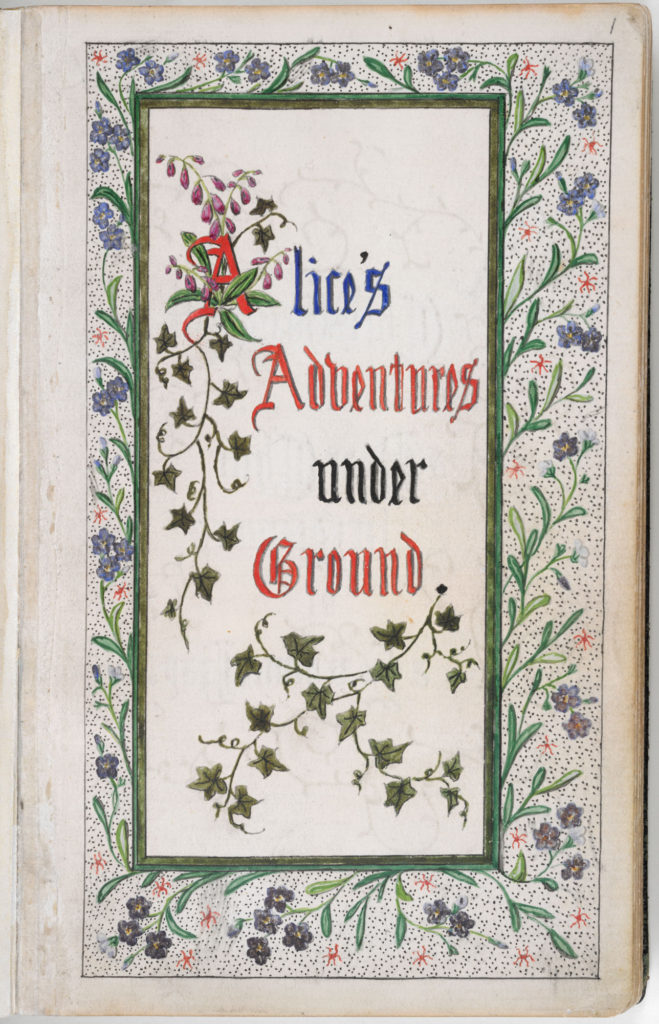

The books originated in stories that Lewis Carroll, whose real name was Charles Dodgson, told the young Alice Pleasance Liddell and her sisters Lorina and Edith during a July 4, 1862 boating trip. The Liddell girls were the daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, where Dodgson was a tutor in mathematics. In answer to a request from Alice that he write the stories down, Dodgson presented her with an illustrated manuscript, Alice’s Adventures Underground, as a Christmas gift in 1864.

This version lacks some of the most famous elements of the book Dodgson would publish the following year under his pseudonym as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The success of that book led Dodgson to publish a sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, in 1871.