Honestly, trying to sit down and write this blog post has been a lot more challenging than I anticipated. All of my other final assignments have just been a regurgitation of facts, so switching gears to form my own opinions has been weird. I can tell you why Pluto is no longer considered a planet and trace the path of Alcibiades’ capricious loyalties all through Ancient Greece. My brain physically ached for a while from so much cramming, although that’s not even possible since the brain has no pain receptors. But, a broad question like “What has the point of this semester been?” is a whole different playing field. I drew a mental blank for three days before I even tried to sit down and write. Continue reading “A Step Back From The Semester”

Who Do You Think You Are?

Throughout both of Lewis Carroll’s works Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, language conventions and linguistics are turned on their head. Commonplace words and phrases are used outside of their familiar meanings, sometimes so literally that attempting to find a figurative meaning can only leave the reader befuddled. One very unique instance where Carroll uses this technique is in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in the fifth chapter entitled “Advice from a Caterpillar.” During Alice’s conversation with the Caterpillar, she is asked two very distinct questions. “Who are you?” and “Who are you?” The same three words, but two very different meanings. The first is exactly what it sounds like. Upon first noticing Alice, the Caterpillar asks her to introduce herself. She has difficulty coming up with an answer for his inquiry, though, having only just finished arguing with herself about whether or not she is really Alice or if she had somehow changed into another little girl. At this moment, her own identity is a mystery to her.

But what is interesting is the second posing of the question.

‘Well, perhaps your feelings may be different,’ said Alice; ‘all I know is, it would feel very queer to me.’

‘You!’ said the Caterpillar contemptuously. ‘Who are you?’

No longer is the Caterpillar asking Alice to identify herself. This question has a bitter edge to it that implies it asks more than a name; the words may have been “Who are you?” but the question was “Who do you think you are?” It is meant as a sarcastic comment, but it raises an interesting question.

Are who you are and who you think you are two different things? And if so, which is more important? Even as Alice stumbles along trying to figure out if she is Alice or Ada or Mabel, is she ever anything other than Alice? Does her belief that she must be someone else make it so? Facing the two questions by the Caterpillar, Alice does not answer either of them because she does not have the answers. She does, however, go on to explain that, out of everything, she would feel more herself if she could regain her old height. Although Alice is still Alice, she sees herself a certain way and finds her security in identity in that self-image. She is not Alice if she does not fit that image, so, at least for her, who she is and who she thinks she is are separate but dependent things. In this way, even if Alice is still Alice, who Alice thinks she is is what matters the most.

Youth

Childhood is Crayola crayons, gooey hands, muddy shoes and swing-sets. It is ABC’s, singing into oscillating fans, and bruised knees. Childhood is often a time defined by experimentation and investigation. It is safe to say that child’s existence is driven by Saturday morning cartoons and the idea that as soon as they stumble out of the doors of that Twinkie-shaped bus, they will be free to explore and play. Adults, on the otherhand, often fill time wrinkling foreheads, checking bank accounts, and making beds in the morning. There is an extreme pressure for adults to maintain an extreme sense of professionalism and realism in their everyday life. Adults are often not encouraged to ask questions, and just do. This polarized, rigid expectation is unhealthy and detrimental. In many cases, this imposed expectation causes adults to obtain a form of escapism, whether it be drugs, or even simply a favorite television show. This idea is most likely is engraved in us because maturity is improperly linked to adulthood. In reality, a youthful mindset has nothing to do with one’s level of maturity.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, otherwise known by Lewis Carroll, was born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury England. After attending Rugby School, and Christ Church (Oxford), Carroll started taking an interest in photography. Many of his photos focused on children because he liked the way that they approached life. He also grew especially fond of the dean of Christ Church’s daughter, Alice Liddell. Alice was the inspiration of both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Continue reading “Youth”

Thursday theme – When You Dream

Today’s theme song in ENGL 203-04 is “When You Dream,” from the album Stunt by Barenaked Ladies, released in 1998. Lyrics here.

The speaker, watching their new son sleeping, asks, “When you dream, what do you dream about?”

Reading the Alice books has made us ask a lot of questions about dreaming. Can I know when I’m awake and not dreaming? How do I know that I’m not part of someone else’s dream? Can the person in whose dream I appear be someone who’s also part of my dream? (Alice proposes just that possibility in the final chapter of Through the Looking-Glass.) Do children have a special relationship to dreams and to the fount of dream-creativity, imagination?

But in Tuesday’s class, we also asked some questions about the word about. What does it mean to say that the Alice books are “about changes?” Or “about the special relationship between children and imagination?” Or “about the inevitably fluid and unstable nature of conceptual categories”? Or just “about a little girl named Alice who has adventures in an imaginary Wonderland and on the other side of the looking-glass”? Continue reading “Thursday theme – When You Dream”

Tuesday theme – Changes

Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is “Changes,” written by David Bowie, first released in 1971, and performed here by the Melbourne, Australia-based Brentwood Duo.

When he died in 2016, The Atlantic described Bowie as “Rock’s chameleonic maestro.” Change, fluidity, and ambiguity — especially in connection with gender expression — were at the heart of the persona he created for himself.

Changes would do pretty well as a one-word summary of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, too, whether viewed through the lens of narrative structure or that of theme.

Carroll’s interest in change undoubtedly springs from many sources. One worth our notice is the Romantic movement in literature. For the Romantic generation of poets, active in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, change was an important theme. (Carroll was born near the end of this period, in 1832). Two of the major British romantics, William Wordsworth (1770-1850) and Percy Byshhe Shelley (1792-1822), both wrote poems titled “Mutability” (find Wordsworth’s here, Shelley’s here). The word mutability, a synonym for changeability, is etymologically related to the word mutation. Another synonym — one that shows up in Bowie’s song — is impermanence.

It’s hard to talk about change without talking about time, which figures prominently in the Alice books from the outset (“Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!” cries the Rabbit). Wordsworth’s “Mutability” speaks of “the unimaginable touch of Time,” linking change to another important theme of the Alice books, imagination. Yet another link connecting change, time, and imagination is the experience of dreaming. “Whilst yet the calm hours creep,/Dream thou — and from thy sleep/Then wake to weep,” says the speaker in Shelley’s poem. Both Alice narratives turn out to be dreams, though it’s far from clear that Alice’s awakening is an occasion for tears in either.

Like Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”, Bowie’s song seems to suggest that we should embrace the strangeness of mutability. Turn and face the strange, like Feed your head, could serve as a one-sentence interpretation of Carroll’s two stories. It nicely captures the idea that we can encounter strangeness simply through self-reflection (“So I turned myself to face me”) — an idea that becomes especially important in Through the Looking-Glass, whose very title symbolically references the possibility of gaining insight through reflection.

In their openness to the unfamiliar, the different, the fluid, the impermanent; in their insistence that identity is always a complicated matter, Carroll and Bowie stand in stark contrast to those who are today seeking to establish new legal rules around gender identity based on the idea that “Sex means a person’s status as male or female based on immutable [emphasis added] biological traits identifiable by or before birth.” These words are quoted in a New York Times article whose headline suggests one possible motivation for the new rules being developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: “Defining Transgender Out of Existence.”

One of the remarkable things about this effort, as reported in the Times article, is the claim that it’s an attempt to define gender “on a biological basis that is clear, grounded in science, objective and administrable.”

Setting aside the confusion here between gender (a social construct) and sex (a biological category), it’s important to recognize that the notion of sex at work in this effort is anything but “grounded in science.”

For an engaging and fascinating look at how complicated the science actually is, have a listen to Gonads, a series produced by RadioLab from National Public Radio. Or, if you only have time to listen to one episode in the series, make it the one below.

As the teaser on the episode website points out, “A lot of us understand biological sex with a pretty fateful underpinning: if you’re born with XX chromosomes, you’re female; if you’re born with XY chromosomes, you’re male. But it turns out, our relationship to the opposite sex is more complicated than we think.” The lead reporter on the episode, Molly Webster, discovers another Molly who exists “in a parallel universe” — or, to borrow Lewis Carroll’s language, on the other side of the biological looking-glass.

Tuesday theme – Windmills of Your Mind

Our theme song today in ENGL 203-04 is “Windmills of Your Mind,” with music by Michel Legrand and lyrics by Alan Bergman and Marilyn Bergman. It’s performed here by Noel Harrison, who sang it as the theme to the 1968 movie The Thomas Crown Affair. “Windmills of Your Mind” won the Academy Award that year for Best Original Song. The title of the 2003 compilation album that includes this Harrison recording — Life is a Dream — suggests one possible connection between the song and our reading for today.

Thursday theme – White Rabbit

Today’s theme song for ENGL 203-04 is “White Rabbit,” written by Grace Slick when she was a member of the short-lived group The Great Society, and performed by her here as lead singer of Jefferson Airplane. This version, recorded at the 1969 Woodstock music festival, is only slightly different from the one on the Airplane’s 1967 album Surrealistic Pillow but quite different from the Great Society’s 1966 live performance in San Francisco. If you’re in the mood for some mind-blowing retro psychedelic TV, you can also watch this 1967 TV performance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Among works that inspire what we’ve been calling follow-on creativity, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are practically without rival. In his 1995 Lewis Carroll: A Biography (Knopf), Morton N. Cohen writes,

. . . neither Alice book has ever gone out of print. . . . Next to the Bible and Shakespeare, they are the books most widely and most frequently translated and quoted. Over seventy-five editions and versions of the Alice books were available in 1993, including play texts, parodies, read-along cassettes, teachers’ guides, audio-language studies, coloring books, “New Method” readers, abridgments, learn-to-read story books, single-syllable texts, coloring books, pop-up books, musical renderings, casebooks, and a deluxe edition selling for £175. They have been translated into over seventy languages, including Swahili and Yiddish; and they exist in Braille.

(pp. 134-35)

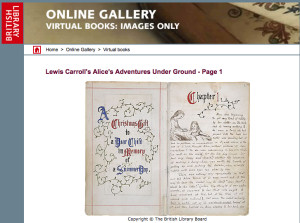

Alice’s Adventures Underground at the British Library

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

The British Library holds the manuscript of Charles Dodgson’s Alice’s Adventures Underground (1864), the forerunner to his Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which he published in 1865 under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. On the library’s website, you can leaf through the 90-page book and view Dodgson’s 37 illustrations. How does the experience of reading the story in this format differ from the experience of reading it in a typeset edition on paper, or as plain or formatted text on a screen?

In class, we discussed the 1903 silent film version of Alice. You can find that at the Internet Archive.