This semester I took a course entitled “The Great War in Literature and the Arts.” The class focused on the novels, music, poetry, and visual arts inspired by World War I. For the course, I wrote a research paper on the German invasion of Belgium that occurred at the war’s outbreak and how its brutality affected Belgian poetry of the era. Much of my research focused on the unjust execution of thousands of Belgian civilians by German soldiers. Reading about these atrocities was extremely difficult, especially since this was my first time learning about them.

In order to glean the invasion’s effect on poetry, I analyzed the work of the Belgian poet, Paul van Ostaijen, who witnessed the German siege of Antwerp and saw the chaotic carnage it produced. As a result of his experiences, van Ostaijen wrote Occupied City, a book of poetry that describes Antwerp at the time of the attack and relays the terrors that transpired.

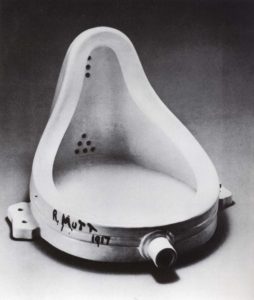

Van Ostaijen’s style was heavily influenced by the Dada movement that was itself inspired by World War I. The word “Dada” means nonsense, a definition that arguably extends to the movement itself. Dada art appeared to be produced without intent; this impression was created through artists’ implementation of the found object technique. Using this technique, art could be created by repurposing random, ready-made materials, such as the urinal Marcel Duchamp used for his “Fountain.”

Though many perceived Dada art and literature as nonsense, Dadaism and its rejection of structure allowed for greater sensation, as can be seen in van Ostaijen’s work. Van Ostaijen’s poem, “Threatened City” rejects the protocols of poetic meter, stanzas, and rhyme. Instead, he writes words and phrases upside-down, in reverse, and in various fonts and sizes. The poem’s disordered configuration describes the chaos and tristesse of the invasion more effectively than a standardized poem would since the happenings it chronicles were themselves incredibly chaotic.

Through analyzing van Ostaijen’s work and researching the events that inspired it, I began to notice that both the invasion and the poetry it inspired could be defined as nonsensical. However, I found that the two do not correspond to the same definition of nonsense. Van Ostaijen’s poems could be described as nonsensical, in that his jumbled structure cannot be traditionally read or understood; the messages of his work can only be conveyed if one accepts the absurd nature of the text.

The Germans executed innocent Belgian men and women of ages ranging from a few months to over 90. Furthermore, the Germans looted and burned many Belgian villages and in one instance expressly burned down a university library. This cruelty represents nonsense in the bleakest understanding of the word.

In reflecting on the origins of the word nonsense, one finds that it comes from the Latin word “sensus” which means “faculty of feeling, thought, meaning.” The violence committed by the Germans was an act of “non-sense” since the Germans abandoned their faculties of feeling, thinking, and meaning; they neglected to empathize with the Belgians, were unthinking in their needless slaughter of innocents, and failed to consider the meaning of their actions and the consequences of such gruesome acts.

The “non-sense” that was committed by the Germans can be best understood through the absurd, non-structured nonsense embedded within van Ostaijen’s work. This principle also extends to Everett’s work, I am Not Sidney Poitier, since Everett grapples with instances of nonsense, as in lack of feeling, through the implementation of nonsense, in its absurd definition. The employment of such nonsense exposes the lack of feeling present in certain aspects of society and effectively represents the extent of this apathy and its consequences.

For example, in I am Not Sidney Poitier, Not Sidney is attempting to drive from Atlanta to Los Angelos, when he is apprehended by a police officer who arrests him for no discernable reason, other than the fact that Not Sidney is black. The cop’s dialogue is nonsensical and his thought-process shows no element of logic or reason. Everett writes the scene in this absurd way to demonstrate that the cop’s prejudices against Not Sidney are themselves entirely nonsensical, unjustified, and born from lack of feeling and thinking.

Not only does the cop exhibit misconduct, through his use of deplorable language and aggression against Not Sidney, but he also displays a complete lack of feeling and thinking. Everett writes this scene in a nonsensical style to expose the lack of feeling that is complicit in the cop’s racism and brutality, as well as the overall senselessness of racism. While the cop’s assertions and actions against Not Sidney may seem ridiculous and nonsensical, they are probably not so different from the veritable experiences of some.

It is often said that one should not fight fire with fire, but perhaps nonsense is the best way to expose and thus combat nonsense. Just as a nonsensical structure and syntax allow van Ostaijen’s poetry to convey the horrors the German invasion wrought on Belgium, Everett’s instances of absurd dialogue expose the senselessness and danger of societal issues such as racism and police brutality.

Although nonsense is an effective technique one can use to expose the nonsense in others and society, one should still remind oneself of the weight that such nonsense holds. Indeed, lack of feeling, thinking, and meaning is responsible for many of the terrors and tragedy that plague humanity today. So, while nonsense is capable of exposing nonsense in the bleakest sense of the word, we should not get caught up in the method’s absurdity, and focus instead on the consequences it reveals.